Study: Fish use as metric for ecological function

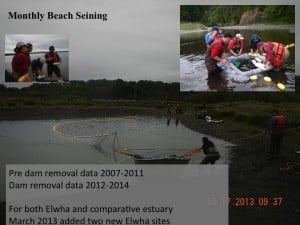

This paper presented an overview of results to date of CWI’s ongoing study to define how nearshore ecological function responds to dam removal sediment delivery through three time phases: 1. Pre-dam removal; 2. Dam removal; 3. Post-dam removal

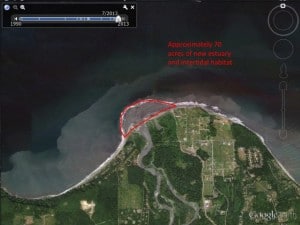

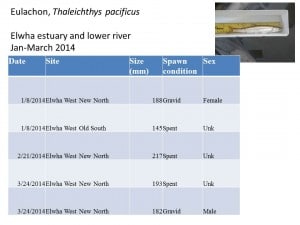

Sediment delivery has just begun. Numbers change daily, but somewhere between 20-60 percent of the 16 million cubic meters (what an astounding number!) of sediment predicted to be delivered to the nearshore has arrived. Physically, restoration has just begun.

Ecologically?

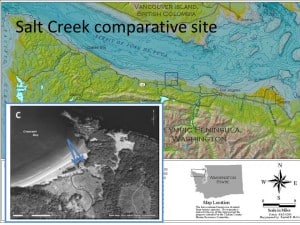

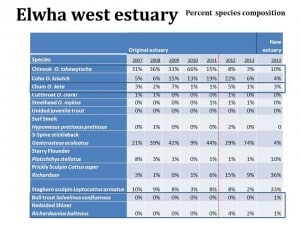

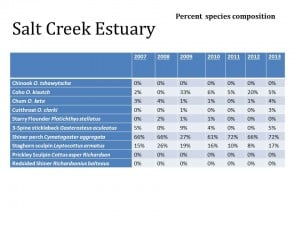

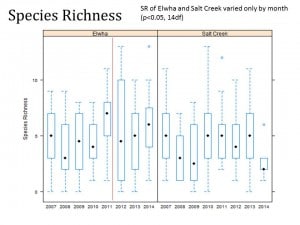

While the story is still unfolding-remember dam removal is not yet complete and sediment is just starting to arrive to the nearshore-we’re seeing the following changes in the Elwha estuary. We attribute these changes with dam removal as we are not seeing these changes in the comparative Salt Creek area.

In a nutshell?

Species Richness is highly variable in the nearshore, and defined by month. Species Richness in the Elwha estuary has not changed significantly since dam removal began, and is not significantly different than that of the comparative area.

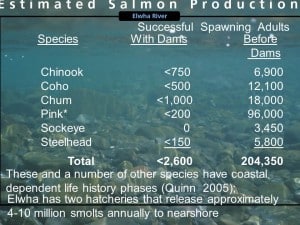

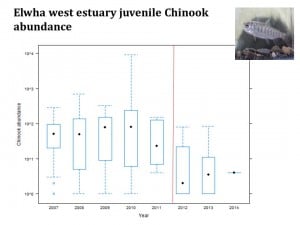

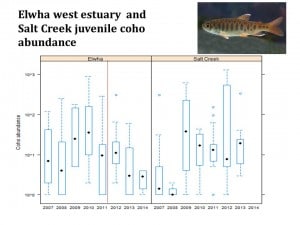

We may be seeing some response in Chinook and coho use of the Elwha estuary-hatchery releases make it VERY hard to decipher….

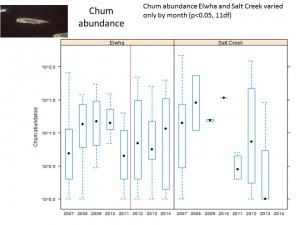

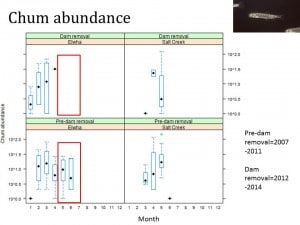

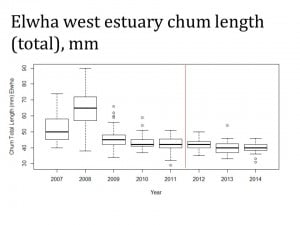

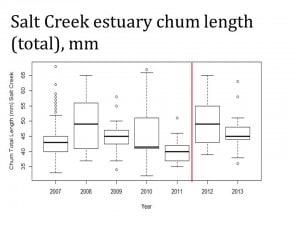

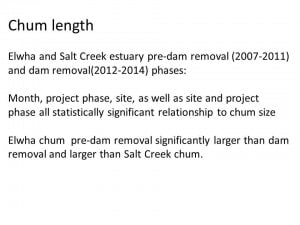

Observations of our chum data are very intriguing. While overall abundance appears to be about the same, when, and the size of, juvenile chum are using the Elwha estuary appears to be changing.

Conclusions

It is vital to stress that these results are preliminary and will undoubtedly change as the Elwha nearshore continues to restore. We will continue to work on these elements in more detail for the upcoming post dam removal phase. Our informal, preliminary observations to date:

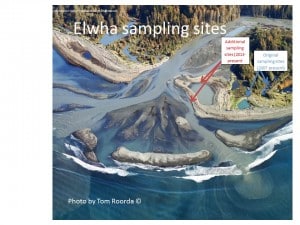

- Overall, ecological function of the Elwha estuary is functioning at pre-dam removal level thru the dam removal phase. New estuary sites functioning at same ecological level for fish as original Elwha sites. As soon as the estuary habitat is available juvenile salmon are using it.

- Elwha nearshore estuary habitat is changing rapidly: both estuary and lower river habitat are expanding. Both changes are reflected in fish use as the estuary and lower river grow.

- Chum use of the estuary may be more complex than initially understood – juvenile appear to be leaving the estuary earlier, and smaller than prior to dam removal. We’ll assess this in more detail once dam removal is over.

- Hatchery releases currently occur at the peak of juvenile chum use of the Elwha estuary. Given the importance of the estuary for restoring chum, and the historic importance of chum to the watershed, chum should be considered in much more detail when considering adaptive managment options for the watershed. We’ll assess this in the near future after 2014 (dam removal) outmigration season and project phase is over.

Thank you to:

CWI volunteer extraordinaire Anne Gough contributed significantly to this blog!

And for some fun footage of juvenile salmon use of the nearshore see our humble video: